About Amazon Kindle

It started with a simple idea and a catchy name and is now synonymous with digital reading: Kindle. The word comes from English and means “to kindle” or “to ignite.”

It started with a simple idea and a catchy name and is now synonymous with digital reading: Kindle. The word comes from English and means “to kindle” or “to ignite.”

Amazon had a particularly lucky hand when launching its eBook platform and was able to meet rapidly growing demand with the right eBook readers. At the same time, the company quickly expanded its digital book selection, putting together an all‑in‑one, worry‑free package for bookworms in no time. The result: today Amazon is the undisputed number one in the global eBook market. The brand isn’t just about electronic reading devices, but a holistic system for selling eBooks.

Amazon wasn’t the first company to release an eBook reader, but the retail giant significantly drove the market forward with the first Kindle. Initially the Kindle appeared only in the USA, but by the third generation it launched in Germany as well. Amazon quickly gained market share there too, partly because competitors were still relatively weak.

Despite ever‑growing competition, Amazon continues to hold the largest share of the eBook (and eReader) market in Germany. The devices are sold primarily on Amazon’s own website, but are also available through local electronics retailers (Media Markt, Saturn).

One thing market watchers notice is Amazon’s swift response to competitors: Kindle eReaders repeatedly undercut Tolino devices by a wide margin. Even strong promotions from rivals are often overshadowed by Amazon with even deeper discounts.

Kindle comparison: Which Kindle should you buy?

Amazon currently offers three different Kindle models in various price tiers:

The three devices target different audiences. Let’s take a look at who they’re for and who should buy which Kindle.

Kindle basic model

The entry‑level model, simply called “Kindle,” is the most affordable way into Amazon’s eBook world. It costs less than the other models but also offers less.

The entry‑level model, simply called “Kindle,” is the most affordable way into Amazon’s eBook world. It costs less than the other models but also offers less.

Strictly speaking, the entry‑level Kindle is no longer fully up to date technologically. That’s most apparent in the display, which uses E Ink Pearl. This display tech is no longer used by any other mainstream eBook reader. You also have to do without a front light, which makes everyday use less convenient than with the other two models.

On the software side, however, there’s nothing to complain about, since all three Kindle eReaders share the same interface.

We can’t recommend this device. Only if you read very rarely and aren’t sure you even want to read digitally should you consider the basic Kindle. But even then, you’re better off with the Kindle Paperwhite.

Kindle Paperwhite as the all‑rounder for everyone

The Kindle Paperwhite 4, introduced in 2018, is a careful and sensible evolution of its predecessor. It impresses with one of the most uniform front lights on the market, a crisp 300 ppi Retina display, and excellent readability.

The Kindle Paperwhite 4, introduced in 2018, is a careful and sensible evolution of its predecessor. It impresses with one of the most uniform front lights on the market, a crisp 300 ppi Retina display, and excellent readability.

It also adds built‑in water resistance and audiobook support. The feel in hand is excellent thanks to familiar materials and a flush front, and the build quality is equally strong.

The Kindle Paperwhite is an easy entry into digital reading and can essentially be recommended to anyone looking to buy a Kindle. It does cost a bit more than the basic Kindle, but the front light, water resistance, and E Ink Carta tech offer clear advantages that more than justify the higher price.

Kindle Oasis with that special extra

The Kindle Oasis is aimed at those who have been reading digitally for a long time and want that special extra in an eReader. Thanks to its asymmetrical design and page‑turn buttons, the Oasis offers even better, more intuitive handling than the Paperwhite.

The Kindle Oasis is aimed at those who have been reading digitally for a long time and want that special extra in an eReader. Thanks to its asymmetrical design and page‑turn buttons, the Oasis offers even better, more intuitive handling than the Paperwhite.

The lighting is even more uniform than the already excellent light of the cheaper model. The screen, an inch larger, and the premium aluminum casing further boost comfort.

The unusual design also makes it more comfortable to hold one‑handed, as the center of gravity is compactly shifted to the side with the buttons.

The Kindle Oasis is an excellent reading device, but given its high price it won’t be the right choice for everyone. Although it has several advantages over the Paperwhite, the surcharge is only justified if you want that special extra. For comfortable reading, the Kindle Paperwhite is more than enough.

Kindle history at a glance

Let’s take a look at the beginnings of the Kindle system, now hard to imagine the digital book market without: Amazon launched its first eBook reader on November 19, 2007. It was a time when digital reading wasn’t unknown but was still rare. There were no extensive commercial offerings yet, and the consumer electronics market was far from today’s mobile boom. The first iPhone was introduced the same year (January 2007).

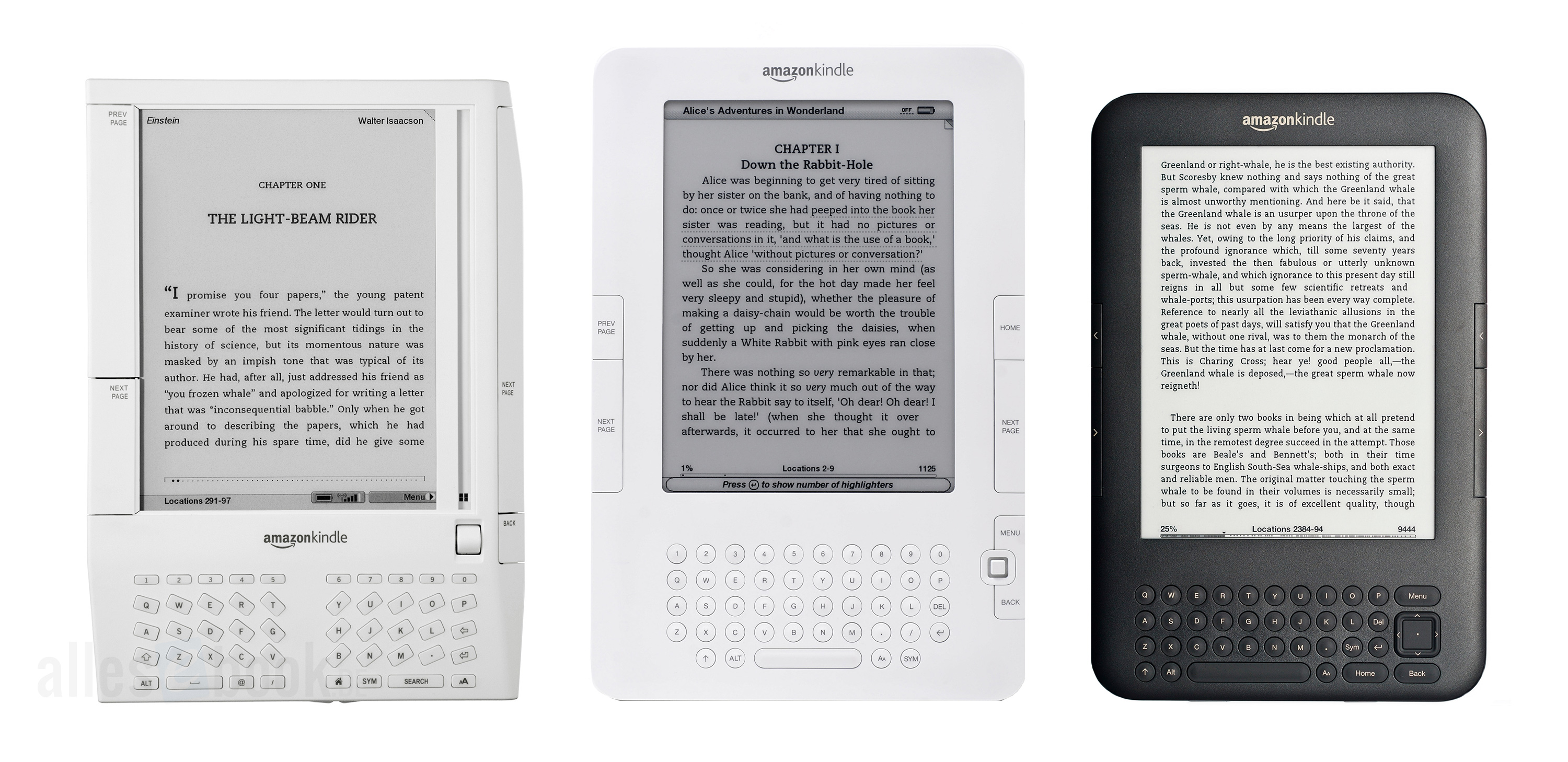

2007 to 2010: Kindle launches

That didn’t stop the first Kindle from being a success: Despite the nascent eBook industry, the device, priced at a hefty US$399, sold out in just five and a half hours. Amazon was clearly taken by surprise by the demand, as it took a full five months for the eReader to be back in stock. It wasn’t until April 2008 that the retailer could offer it again.

To this day, it’s the only Amazon eReader with a memory card slot. All subsequent devices rely on internal storage and the increasingly important cloud storage. eBooks, which could already be purchased directly on the Kindle (other devices in Germany didn’t get this until 2011), were immediately available via Wi‑Fi or 3G and could therefore be accessed from virtually anywhere.

Even then, Amazon’s first eBook reader laid the foundation for the now standard 6‑inch format. It wasn’t the very first digital reading device (that honor goes to Sony with the Librie), but it was the most successful of its time. There was no reason to deviate from the winning formula, so all subsequent generations (including those from other companies) primarily stuck with 6‑inch screens.

Plans for European expansion initially failed due to missing mobile contracts. The Kindle—as mentioned—featured 3G support. Since this wasn’t supposed to incur additional costs for customers (still true for current models), Amazon had to negotiate the contracts itself. That didn’t work out until the end of 2009.

At the beginning of 2009, Amazon introduced its new eReader, again under the same name. As Apple had done with the iPhone, Amazon clearly wanted to strengthen the brand name and market the devices without confusing model names. The new model wasn’t exactly a bargain either at an initial price of US$359. The price soon dropped to US$299, and in October, when the international version launched, it fell to US$259.

Estimated production costs were around US$185, meaning Amazon wasn’t selling at cost. Only when the largest US bookseller, Barnes & Noble, cut the price of its own eReader (Nook) in June 2010 did Amazon follow suit and sell the Kindle 2 for US$189. For Amazon, the price cut wasn’t especially painful, since the real profit was always intended to come from selling content, not devices.

2010 to 2012: Kindle grows up

In 2010 the Kindle 3 (later called the Kindle Keyboard) hit the market. It’s likely Amazon’s most successful model to date and marked the breakthrough of the eBook market in the USA. Amazon stayed true to the original concept but significantly improved the E Ink screen, which helps explain the rush. The Pearl technology used at the time still appears in many devices today and delivered excellent readability.

In the meantime, Amazon also released two large‑format models called Kindle DX, whose 9.7‑inch screens were intended to appeal to newspaper readers. However, they never really caught on, partly due to a lack of content, and disappeared as tablets rose to prominence.

In 2011 the Kindle Keyboard finally came to Germany, though the launch likely happened more out of a need to establish a presence in the German market than to win customers. The eReader was sold without German localization, i.e., the interface was available only in English—hardly ideal for success in Germany.

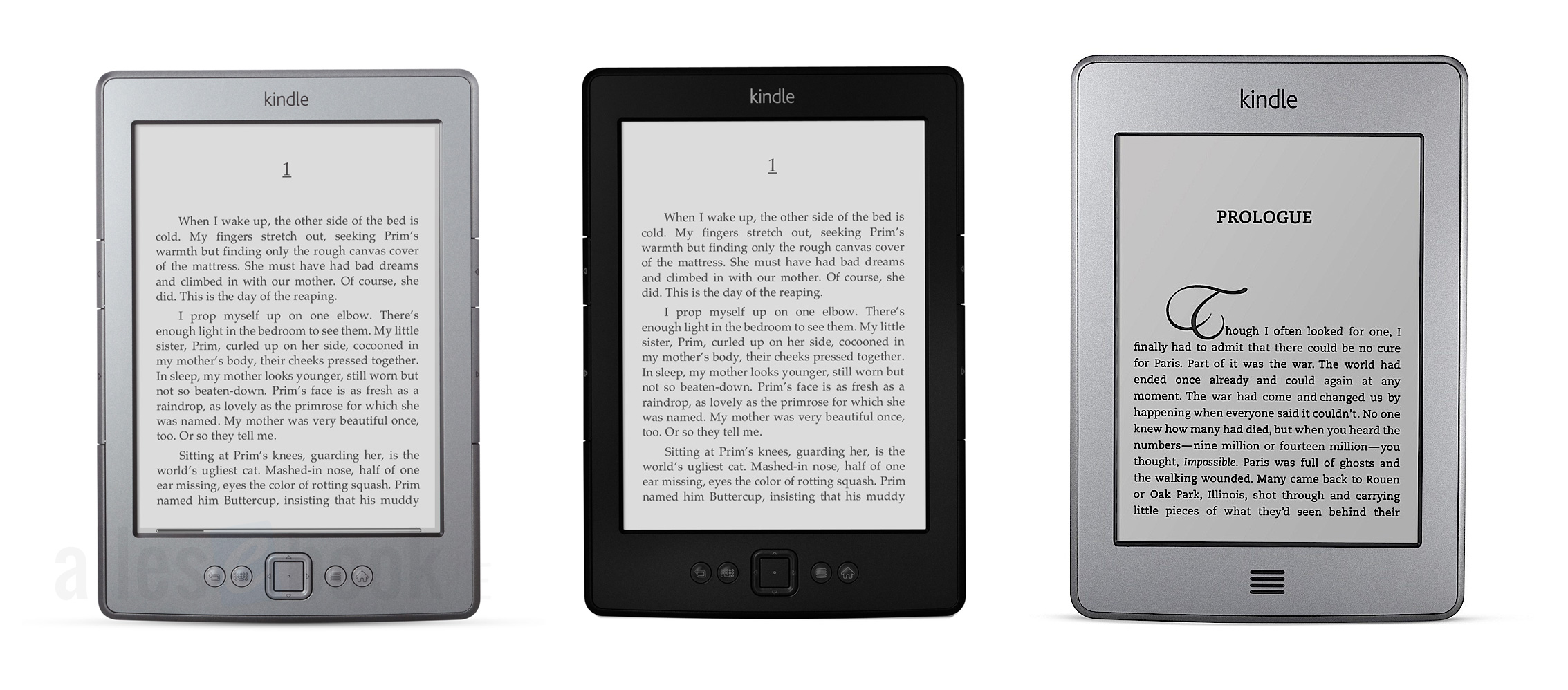

The basic model (left) was replaced a year later by the new model (center) with a redesigned look and improved screen. The Kindle Touch (right) was available in Germany only for a relatively short time.

Later came the new basic model, which finally scored points with a localized interface, and by 2012, when the Kindle Touch arrived in Germany, it was clear Amazon was as serious about expanding in Europe as it was at home. However, since the company’s first touchscreen eReader hit the market here with a delay, it was replaced after just a few months by Amazon’s first front‑lit eReader: the Kindle Paperwhite 1.

2012 to 2015: The Paperwhite era

It wasn’t all smooth sailing, though. The Paperwhite initially had issues with front‑light quality, leaving many customers with visible color blotches. This led to an unprecedented wave of returns. It was likely a painful experience for the retailer. Nevertheless, Amazon celebrated enormous success with the new device, because even frequently exchanged units eventually pay off, and the odds were good that the new customers acquired then would remain loyal to the Amazon ecosystem.

Only after a few months—at the start of 2013—did Amazon get the issues under control. From then on, sales seemed to go smoothly without further outcry. In late summer 2013, the Kindle Paperwhite 2 was introduced. It didn’t suffer from the issues of its predecessor and, for a long time—even against growing competition—boasted the best display.

That was thanks not only to the now trouble‑free front light, but also to the first use of E Ink Carta, which delivered even better readability than the previously common Pearl tech. In June 2014 Amazon quietly refreshed the Paperwhite 2, doubling internal storage to 4 GB.

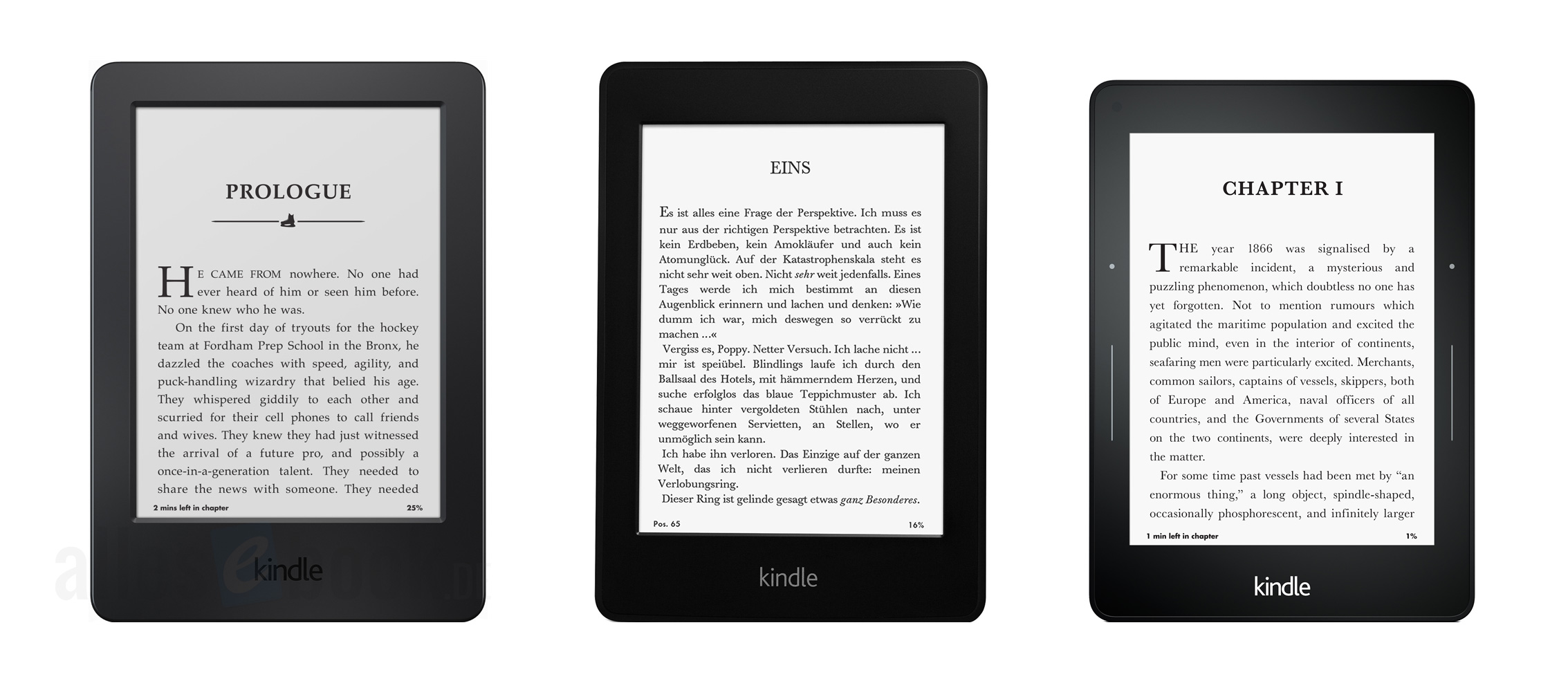

In September 2014, Amazon replaced the entry‑level model with a new basic Kindle featuring a touchscreen. It was essentially an unlit Paperwhite in a new housing. A high‑priced premium model also hit the market: the Kindle Voyage, combining a particularly high‑resolution E Ink Carta display with a light sensor and pressure‑sensitive page‑turn buttons.

With the introduction of the new product generation, an interesting change also occurred with the tablets. Instead of keeping them under the Kindle brand umbrella, they’ve been marketed separately as “Fire” devices ever since. Amazon wanted to differentiate the eBook business more clearly and establish the Fire brand just as it had with eBooks.

In summer 2015, there was an update to the Kindle Paperwhite. Like the Voyage introduced a few months earlier, the device received a high‑resolution 300 ppi display, which proved to be a great improvement in our testing. This was due not only to the better tech, but also to expanded typography options introduced with new firmware.

2015 to 2018: The audiobook era

The years from 2012 on were marked by an intense price war in Germany. The wider availability of eReaders from Sony, Bookeen, and Kobo, as well as the launch of the Tolino alliance in 2013, led to unprecedented competition in the German eBook market. As a result, device prices fell steadily over time.

The higher‑priced Kindle Voyage (see above) can be seen as a partial response to falling device prices. Like other manufacturers, Amazon attempted in 2016 to establish an even more expensive device class. The Kindle Oasis 1 was priced significantly above the Voyage, which didn’t thrill all customers. Nevertheless, the first Oasis became a popular reading device thanks to its unusual design, premium leather covers, and outstanding feel in hand.

Kindle Oasis 2

After just a year, the high‑end Kindle was replaced by its successor, which retained the key advantages and addressed many criticisms. The Kindle Oasis 2 has a larger battery, is no longer bundled by default with a cover, and is therefore cheaper to purchase.

It also features a screen larger than 6 inches for the first time since the Kindle DX. With a 7‑inch display, Amazon followed competitors who had long been offering larger models.

Built‑in water resistance and audiobook support (via Bluetooth and Audible) round out the package. The Oasis 2 is available in three versions (Wi‑Fi 8 GB & 32 GB; 3G 32 GB) and still only in ad‑free configurations.

Kindle Paperwhite 4

In 2018 the Kindle Paperwhite 4 was introduced, replacing the long‑running Paperwhite 3. Observers had been expecting the change (a photo of the device surfaced in 2017), as the gap with competitors in the mid‑range segment had been narrowing for some time.

The new Paperwhite brings audiobook support, built‑in water resistance, and a flush front. The rapid price drop for the 2018 holiday season was a particular surprise. For Cyber Monday/Black Friday 2018, the new Kindle was already about 40 euros cheaper.

The new Kindle Paperwhite isn’t available in multiple colors yet, but it does come in five different versions—ad‑supported or ad‑free, with or without 4G, and with 8 GB or 32 GB of storage.

Before the new Paperwhite launched, the Kindle Voyage was discontinued. The decision likely had to do with the devices’ technical proximity: compared to the Paperwhite 4, the Voyage had few remaining unique selling points and was in some ways worse equipped (no water resistance, no audiobook support). It would be a surprise if Amazon didn’t give the Kindle Voyage a successor despite its years of success. 2019 could be the year.

Kindle ecosystem

As mentioned at the outset, Kindle isn’t just a hardware solution, but a comprehensive software and service ecosystem. In everyday use, there’s essentially no other eBook offering that works as seamlessly across devices as Amazon’s.

The retailer offers Kindle reading apps for all major operating systems, making it easy to sync eBooks and reading progress without technical know‑how or effort.

Another highlight is “Whispersync for Voice.” Behind the cryptic name is synchronization of reading and listening progress between eBooks and audiobooks. In other words: if you’re reading an eBook and then switch to the accompanying audiobook, it picks up right where you left off in the eBook. And vice versa.

It doesn’t work with every eBook yet, but the number has been rising rapidly for years—especially for English‑language titles. Many German eBooks and audiobooks are now included as well, so you can often use this unique feature with popular titles. The only deterrent is the price: to use Whispersync for Voice, you have to buy both the Kindle eBook and the Audible audiobook.

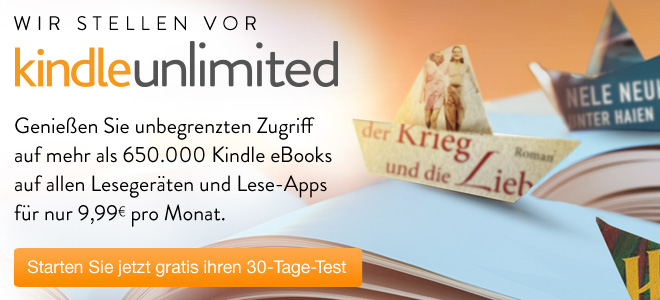

Lending Library and Kindle Unlimited

The Kindle Lending Library is a perk Amazon introduced for all Prime members to further strengthen its offering. Prime is a membership (billed annually) that brings various benefits to Amazon customers (including faster shipping, video and music streaming, etc.).

The Lending Library lets you borrow up to one eBook per month, with no time limits or waiting lists (as with Onleihe). However, it’s worth noting that the selection consists primarily of self‑published titles, so it won’t have the right eBooks for everyone.

With a €10 eBook flat rate, Amazon aims to win over heavy readers

In October 2014, Amazon also launched Kindle Unlimited in Germany. This is also an eBook lending service, but available only as a standalone subscription at €9.99 per month. The big advantage over the regular Lending Library is that you’re not limited to one eBook per month (or at a time), so as a heavy reader you can get a pretty good deal for just €10 per month.

Here too, however: the selection is largely self‑published titles, although some publishers participate. In any case, this eBook flat rate is considered a milestone in the digital book market, as it clearly shows that the demands on booksellers are constantly changing and the digital market is uncharted territory for everyone involved.

Self‑publishing: Kindle Direct Publishing

A key innovation Amazon brought to market with its eReaders is called Kindle Direct Publishing, or KDP for short. It’s a self‑publishing platform for (independent) authors. In plain terms, this means that as an author you can publish your eBook directly on Amazon without going through a publisher.

KDP is the most successful self‑publishing program worldwide and has ensured that the share of self‑published eBooks has reached a critical mass in the overall book market (in the USA). This development isn’t particularly welcome for publishers—on the one hand because it’s hard to compete with typically cheaper self‑published titles (as is very evident in Germany from the bestsellers on Amazon), and on the other because Amazon has direct access to thousands of authors and can easily sign successful ones to bolster its own publishing program.

Even so, KDP is undoubtedly a major value‑add, as it gives unknown authors a chance to be discovered. The path to self‑publishing isn’t always easy or successful, but there are quite a few successful self‑publishers who were initially rejected by traditional publishers and have now managed to make a career as authors via this new route.

KDP titles appear right alongside the rest of Amazon’s eBook selection, so customers generally can’t tell at a glance whether a book comes from a publisher or is self‑published. There are now over half a million titles, especially in the English‑speaking market.

Criticism of Kindle

As an eBook pioneer, Amazon hasn’t only received praise—it has also drawn a lot of criticism, particularly due to its ever‑growing, near‑monopoly scale. Not only in eBooks but also in the print market, Amazon has long been an indispensable heavyweight in Germany. Estimates suggest Amazon controls about 20 percent of the German book market, which makes it necessary for publishers and authors to be present on Amazon.

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that Amazon’s harshest critics were once criticized themselves: the large German bookstore chains, with their aggressive expansion, crowded out small, independent bookstores. It’s rather ironic that these very chains are now among Amazon’s loudest critics—and that the rest of the book trade has since made peace with the chains (which have been shrinking their footprints again).

Dispute over terms

According to several media reports, in mid‑2014 Amazon leveraged its large market share to demand better terms from various publishers. Specifically, it wanted lower eBook prices, which Amazon said would pass on the inherent cost savings of digital distribution to customers.

In the USA, this meant eBooks should be offered for a maximum of US$9.99 instead of the sometimes customary US$14.99 or more. Amazon also published a statement in its own forum to make its demands more understandable to users (and authors): for every eBook sold at US$14.99, an average of 0.74 more would be sold at US$9.99. Instead of selling just 100,000 copies at US$14.99, at US$9.99 you’d sell 174,000—far more. In such a case, revenue would be 16 percent higher at US$1,738,000 (instead of US$1,499,000). Customers would pay 33 percent less, and authors would reach an audience 74 percent larger.

Because eBooks have no printing costs, no risk of overprinting, no need for forecasts, no (B2B) returns or lost sales due to out‑of‑stock items, no warehousing or transport costs, and no used‑book market, they should of course be cheaper than paper versions, says Amazon.

There’s a problem with that math, though: the number of readers is finite. Even if a title sells better at a lower price, it doesn’t necessarily mean a publisher or author will do better overall, because it could just as easily reduce sales of other books. The impact on the print market is also unpredictable; losses there could invalidate Amazon’s equation.

And lastly—and this is probably publishers’ biggest worry—Amazon’s market power would grow further. The dispute earned its name not only because the retailer haggled with publishers over prices, but also because Amazon kept titles from affected publishers in its catalog with delayed delivery. That, of course, led to revenue losses and drew heavy criticism.

Here is a timeline of events surrounding the dispute over terms.

DRM and the lack of EPUB support

A constant topic with eBooks is file copy protection (DRM). It’s intended to prevent unauthorized sharing and duplication. Its usefulness is debatable, however, since most DRMs can be bypassed with minimal effort. Amazon’s KFX files can now be cracked as well.

Laypeople usually aren’t aware of the technical possibilities, and of course removing protection is not permitted under German law, so criticism of DRM use remains valid. The issue with Amazon is the use of proprietary protection, i.e., its own software solution that no other provider supports. That means DRM‑protected Kindle eBooks can only be read on Amazon devices or with Amazon’s software (e.g., for Android or iOS).

This is a very effective way to lock in customers, because once you start buying eBooks from Amazon, you’ll likely keep doing so. If you want to switch to another provider, you can’t take the DRM‑protected part of your library with you.

The flip side is that as a customer you don’t have to worry about anything. Everything works without tech savvy and without registering with a third party (Adobe).

Status quo and outlook

As noted several times, Amazon is now inseparable from the eBook market. For all the criticism—much of it justified—Amazon also deserves credit for driving the new book format forward. The company clearly read the signs of the times and aligned its entire offering early. German providers waited far too long and stood by idly, which is partly why we have today’s situation with Amazon as market leader.

Better late than never, the Tolino alliance formed in 2013 and, thanks to strong backing from local chain bookstores (Thalia, Weltbild, Hugendubel), quickly rose to number two in Germany. The gap with Amazon remains, but it’s narrowing.

Amazon’s decisive advantage—and likely one it will retain—is the KDP self‑publishing program. This has made Amazon the go‑to destination for independent authors, and despite efforts from a number of smaller competitors (and Tolino), that’s unlikely to change anytime soon.

Regardless of how you feel about Amazon and Kindle, it’s clear the global eBook market wouldn’t be where it is today without the retailer’s relentless push—both technologically and in terms of content. And since several providers are competing for customers in Germany in particular, one party stands to benefit most in the end: the customer.